In guise of an artistic manifesto...

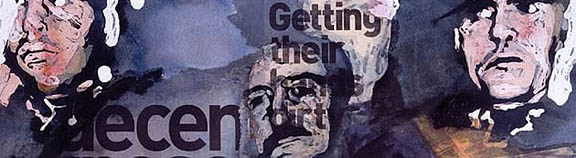

For several years now in the artistic community, the adjective « contemporary » has raised debate and controversy. Does it apply to all that is “of this time” or is its meaning limited to “what makes art move forward”? Today the dominant discourse, the official discourse, only seems to apply the label “contemporary” to artworks which conform to a certain number of unwritten rules and criteria. Technocrats and cultural managers, who don’t have any artistic practice, use it in a consensual, exclusive way. Their one-sided discourse has metamorphosed itself into ideology.

We find it hard to accept this dominant and dogmatic discourse. What right do technocrats and cultural functionaries have to impose context, hierarchy and the definitions of today’s artistic production. What authority do they have to so direct art criticism? With what criteria do they exclude certain types of material used to make art works considering them outdated? To merit the label of “contemporary” given by cultural technocrats, the only thing that seems to be taken into account is what a work is made of – or rather with what it shouldn’t be made of.

How often does the artist who admits producing painting on canvas or sculpture with wood have his / her work rejected by a technocratic employee of a cultural institution even before he / she can explain the project. In the realm of contemporary art, the meaning or the message of the work seems a secondary criterion when it is question of evaluating artistic worth. And of course, for the technocrats who decide, it’s completely futile to talk about the aesthetic dimension in a work of art. For them, that is the definitive sign of outdatedness.

Their “contemporary art” often transforms the art object into a fetish. As proof we only need to look at the innumerable “installations” centred around an object “infused” (by the artist) with history: a used tampon, a brick from this or that wall, a torn photo in a cardboard box, the television screen showing a never ending cycle of static electricity from the universe…The public is invited to specially NOT appraise the object for its aesthetic reality but to reflect upon what it represents. We will then be asked to fill this gapping space left open for “reflection” with discourse taking the spectator far from the realm of sensation. From then on the artwork only exists an expression of the discourse grafted onto it. However, the artists making installations often say that their work is not an art of representation; nor is it an object to be admired aesthetically. So we ask a simple question: What is it then?

One of the major problems in the art world today resides in the difficulty to apprehend the world that is being structured around us, to seize hold of the new divisions that are shaping it. However we refuse to fall into complaisance, or cynicism which makes every artistic proposition emptier than the next, its importance inversely proportional to the weight of its verbal (or verbose) justification and structured discourse. We don’t want to be simultaneously victims and accomplices of a process whose intention is to eliminate all artworks that don’t conform to this sort of grafted empty discourse.

We would like to raise the level of debate around contemporary art to a level where it would be possible, without being accused of blasphemy, to disagree with an artistic proposition which, for example, proclaims as exultant stripes placed 8,7 cms from each other as in Daniel Buren’s work.

In the late sixties, Marshall Macluhan stated that “the medium is the message”. We would like to think that the message in the artwork could be found elsewhere than in the materials used to make it, but also that the message be legible in the work itself, not a crutch pinned on a wall next to it. We have something to make and to say independently of the medium used to make the work.

In the fight against the escalation in vacuity in art and in society in general, we have a duty to structure meaning.

Collectors who buy works of art by an artist working outside the dominant discourse often have an emotional even passionate relationship with the artwork: they can speak of falling in love with the artwork. We don’t dismiss the emotional aspect behind art. Art can also be beautiful.

Tired of the hermetic schools, tendencies and cenacles in art, refusing broad reaching judgements and a priori classifications, we believe in an art which is open to all forms of expression and supports, provided that it bears the seed of real desire to communicate and to generate thought and reaction.

We hope that our work fits into a long-term perspective of artistic expression outside of ephemeral tendencies. The only urgency for us determining our approach is the desire to communicate with a real public, capable of thinking and feeling.

Bruce Clarke